Completely (Un)finished: The Life and Works of Katharine Modán[...] - Luke Buffini

- SHORT FICTION

- Dec 1, 2020

- 12 min read

Completely (Un)finished: The Life and Works of Katharine Modán, An Introduction

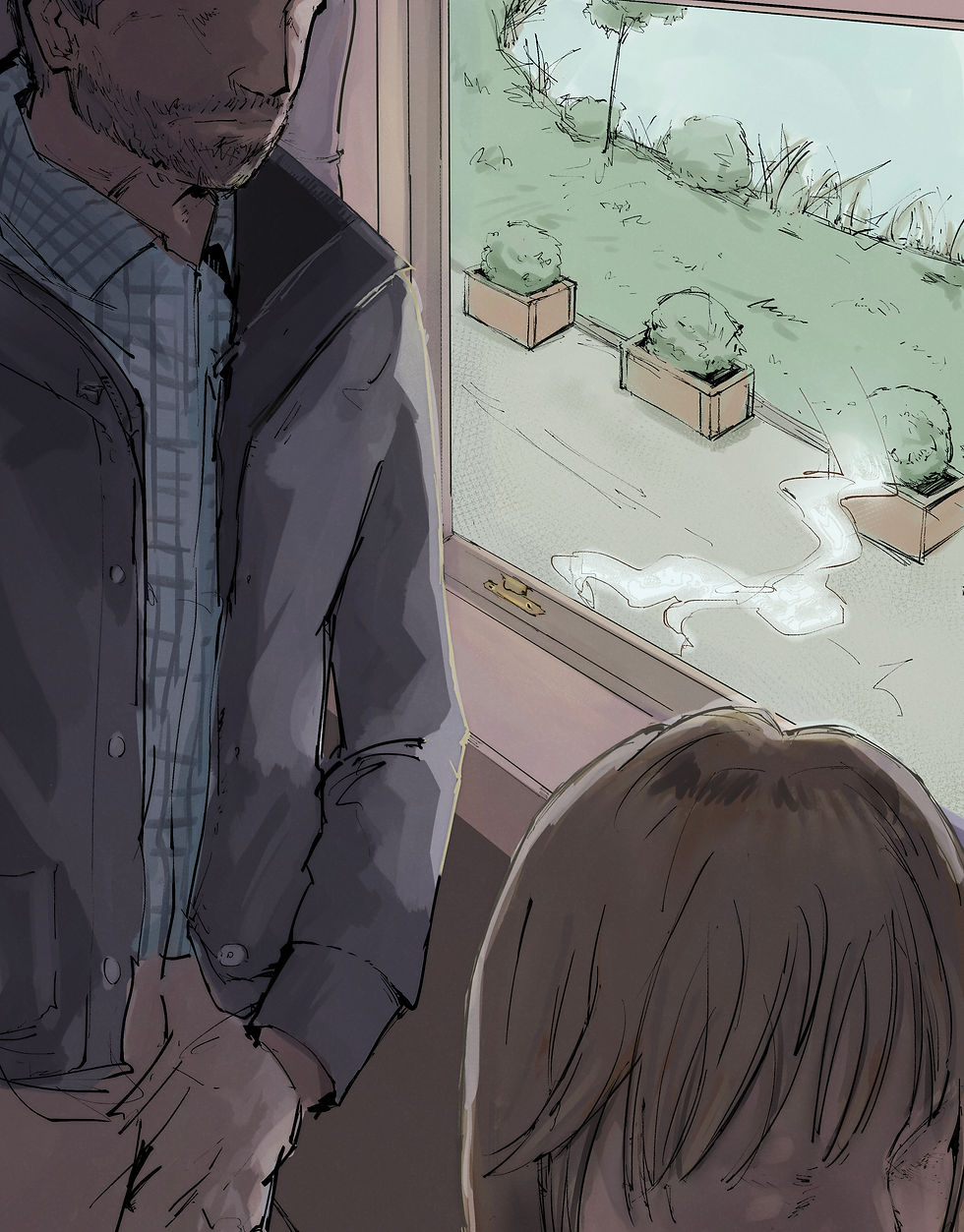

The first time I saw her was October 6th, 1997. I remember because it was the date we started lectures every year. I was in the King’s College cafeteria, eating lunch. At the far end of the room, by the large windows looking out on a half-built stone courtyard, she was playing two games of ping pong at once. Two tables had been shoved up alongside each other to create one big table. Katharine was standing on the far side, from my perspective, her back to the windows, meaning I could see her face. Across from her were two other students (one of whom, readers may be interested to learn, went on to become the famous and acclaimed one-word novelist, Patricia Salvador). She was playing two games of table tennis – one with each opponent – simultaneously.

For those who are familiar with Modán’s now-famous work routine, it may come as a surprise that what was so striking about this scene was how spectacularly she was failing at her dual task. To become known, in later life, for her capacity to multitask – writing many books at once – here she exhibited no signs of predestination. To begin with, she would serve on the right-hand table, return perhaps once or twice, then hear the call from the left-hand table to prepare for an incoming serve, move over and return that one, thus missing the next return in the first game altogether, and consequently, when the first opponent’s complaints drew her attention, missing the next ball from the second opponent. Within five minutes she was serving on one game and then moving straight to the other to serve: both games ended every time within seconds. Her friends were at first livid with frustration, but quickly fell into fits of laughter. It took the slightest thing to draw her attention to something else. Passers-by. A stain on the table. Even the most basic attempt to play in a committed manner would have produced results twice as good. But such is the unique approach to life of Katharine Modán.

In the weeks following that first and peculiar observation, I would often see her in the library. We were on the same course – Contemporary and Classic Literature – and thus dedicated a lot of our time to the same four or five feet of that grand old building on Chancery Lane.

There would be me: hacking through The Trial, or Don Quixote, or Infinite Jest –depending on what time of year it was (and never all at once!). And there would be her: six or seven books already open on the floor, none turned past the tenth page, scanning the bookshelves urgently, as if for an answer, taking a hardcover down, examining but not opening it, putting it back, drawing out great tomes of Homer and Virgil, gathering the gist in the first several paragraphs and then returning them to their shelves. It was fascinating and uncomfortable to watch. I would sit at a nearby desk, clawing my way up the prose of whatever looming masterpiece I was attempting at the time, looking over at her again and again. She’d be taking up most of the floor with the books she had discarded just that day. Other students who wanted to use the shelves had to edge around her. But they were too charmed to be annoyed.

It was her friend Patricia to whom I first spoke. I was too nervous to cut in on one of Katharine’s manic library sessions. I think I was scared I might be discarded just as quickly as one of those books. Consequently, it was Patricia who explained about the car accident in childhood, the brain trauma, the damage to the frontal lobe, how all this had affected her behaviour and perception. But it wasn’t until Katharine and I started dating, and the years following that, that I really understood the way she experienced the world.

How can I explain this? She didn’t know that Edward Norton was Tyler Durden. Nor, in fact, that Kevin Spacey was Keyser Söze. She knew ‘Fair is foul, and foul is fair’ and ‘Is this a dagger?’ but not ‘Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow’. To her, the animals had ousted Mr Jones, taken over the farm, and that was the end of it. She didn’t know Napoleon ended up at Jones’ table. She realised neither that Stanley raped Blanche; nor that George shot Lenny in the head; nor that Willy Loman killed himself. She thought Desolation Row was the greatest piece of Pop-lyricism ever written based purely on the first two verses; she never listened to the other eight. You see, Katharine could finish nothing. She had finished no books, no films, no albums and no songs. Somehow her condition prevented her. Thus her mind was composed purely of beginnings: liberated of endings. She knew nothing of catharsis, resolution, disappointment or circularity. In her imagination, the art of storytelling was the same thing as the practice of beginning a story.

The influence this had on her subsequent work will no doubt be known by many readers. Her revolutionary book, The Art of First Sentences (2015), which followed her equally popular if too protracted The Art of First Paragraphs (2011), and won her both the Hitchens and Smith prizes for Exemplary Nonfiction, was an astounding example both of the intensity of her vision and the breadth of her reading. I wonder if any scholar in the world has read as many first sentences as Modán. In it she remarks, with typical wisdom, how the genius of Orwell’s Animal Farm is that the first sentence foreshadows, and so contains, the entire narrative arc:

The mention by Orwell that Mr Jones was ‘too drunk to remember to shut the pop-holes’ conveys in a single detail the carelessness, neglect, and blindness which is to culminate with the animals’ victory and taking over of the farm.

Readers of course must allow for the fact that Modán has never read past Chapter II, and so is referring here to only the first battle between Jones and the animals, where in her mind the story ends.

Elsewhere, she indicates her impatience with the outmoded, epistolary realism of some gothic horror:

Because of Bram Stoker’s insistence on implanting in us the feeling that his story is drawn from real documents, we are given the briefest of first sentences: ‘3 May.’ Some scholars have made allowances for the book’s age, claiming that we must contextualise Dracula in accordance with the psychology and habits of its readers. But the reality is we are only able to judge a book with our own minds. As such, I would point out that an indulgent style content to spend its first sentence in such a trivial way cannot hope to hold the attention of the fickle modern mind.

She spends no more than a paragraph on any one novel and of course, like all her books, and in her signature style, the book ends in the middle of a sentence, precisely at the moment she abandoned it for another project.

Perhaps she is at her most memorable on the early twentieth-century modernists, with whose brevity she always felt a kinship. In one of the lengthier passages in the book (an incredible nine sentences) she lyricises over the famous opening to Camus’s L’Etranger, and explains how much is sacrificed by translators who mark a full stop after ‘Mama died today’, rather than a semicolon. But it is Kafka of whom she thinks highest, and who, she points out, in a characteristically frank assessment, always began his stories ‘at the beginning’:

Kafka’s masterstroke is to create the sense that his characters have only just come into existence in that first sentence.

By comparison, Modán’s masterstroke, in her own fiction, is to demand exactly from her readers what they can afford to give, and no more. Beginnings (2009) provides us with a unique premise. Each of the twenty-one chapters represent the initial pages of a totally different novel, none of them connected, none resolved, and all masterful in their execution. In chapter eight, we discover Don, the cricket-playing intellectual with a thought pattern of Wallacerian neuroticism. We never make it past his anxieties over getting out of bed that morning. Then, in chapter sixteen, we meet Doctor Victoria, the brilliant Swiss computer engineer, working frantically on her life’s work: a humanoid robot whose memory and perception of the world is based on the Doctor’s own social media accounts. Though we anticipate the inevitable tragic outcome, never does that creation stir into life, shudder with the ecstasy and horror of existence, nor destroy its creator in repayment, for Modán leaves us at the eleventh paragraph. Choosing one of these is like choosing your favourite child. But I have a special feeling for chapter four: the story of the ill-fated love of two teenage boys in modern Malaysia, written in iambic pentameter, and told, in its entirety, in a fourteen-line prologue by the chorus. Candice C. Davids, writing for the Times Literary Supplement, says of Beginnings:

Modán’s whole art is to balance perfectly on the tightrope of the modern reader’s attention, and to dismount before that attention snaps beneath her. Asked to name the writer who bears the sort of relation to our era that Sophocles, Shakespeare, and Dickens bore to theirs, Modán is the first I would answer.

#

I have been asked countless times over the years, by journalists and fans, what it was like to briefly live with and love such a woman (a question which, to any writer worth his ego, will always prove a tad irksome!). We were both private to the point of paranoia, knowing – as Katharine herself put it – that publicity would be ‘a beginning whose end we could not dictate’. Even after we split I refused to say a thing about her in interviews or in my own writing. It is only now, writing this introduction, that I feel comfortable divulging any such information. For it is only now I can feel sure that what I say will have no degrading effects on the colossal reputation she has amassed over her career.

In the first two years of our cohabitation, she was content to live in London. The one condition being: we never settle in a single area for more than a few months. We lived with my family in Hillingdon; then with friends (another couple from King’s College) in Brixton; then rented alone in Dalston; this was followed by a brief stint of couchsurfing around west London, before finally we settled in Highgate for a full six months. This was to be the longest we ever lived in one place. After that, we permanently took to the road, moving around the UK for six months, and then onto Europe, Asia and South America, never staying in one city or town for more than a month. At the peak of her career, when money became no issue, we were flying to a new country every forty-eight hours. It was exhausting at times, maddening at others, but there was simply no other way for Katharine to live.

Our relationship was a perpetual honeymoon period. She was intensely romantic, spontaneous, and affectionate. Of course, she had many love affairs over the years. More than almost anything else, she desired new romantic beginnings deeply and continually. However, as those who read My Beginnings: A Thousand Tiny Personal Essays (2019) will know, she had come from a conservative Roman Catholic family. The only hangover of this seemed to be the unextractable belief that it was a great moral failing to sleep with someone on the first date. She always forgot about these affairs after that first meeting, and so she was never once unfaithful, though she continued to dine out with other men regularly.

In day-to-day life, she displayed, on the one hand, a truly staggering inconsistency in everything she did. She was unable to finish anything—even the most trivial things conceivable. Yet on the other hand, there was a formidable, almost inhuman consistency to all this in its own right. It wasn’t so much that she lacked mental stamina or commitment. Quite the opposite. Once you perceived her way of seeing and doing things, you could understand that she was entirely persistent with them.

She gorged herself on aperitifs and starters, but never once sat long enough to receive a main. From what I could tell, she didn’t understand the concept of pudding.

She would fly into a rage if ever I tried to fast-forward through the first few minutes of a film. Even if we’d seen those initial minutes ten times and hadn’t yet seen anything after.

She despised evenings, and always endured them with dreadful anxiety, as if each were the calm before some great and terrifying upheaval. Even when I met her at the age of 19, she would go to bed no later than 9pm, and rise every day at 5am.

Once, sleepy and unthinking, I let slip that Frodo and Sam were eventually to be divided by the departure of the former ringbearer for the Undying Lands. She didn’t speak to me for three days. At the end of the third, she turned to me in bed, and said quite simply: ‘It is a great evil to spoil a good story by ending it.’

#

I turn now to more sombre questions regarding Katharine and her condition which, I hope, will help those readers still confused and hurt, as many of us are, to understand why things turned out the way they did.

Of course I realised quite early on that our relationship could never be permanent; indeed, I was surprised it lasted as long as it did. Our extensive travelling together was no doubt an unconscious compensation for the self-denial she made every day by staying with me. When the end did come it was painful but natural, and knowing her as I did, I was able to see that it was less a choice on her part, and far more a fundamental compulsion of her manner of living. I was able to accept with relative ease that I would no longer be her romantic partner. But what I could not tolerate was to be extracted from the life of this enthralling woman entirely, and by maintaining correspondence with mutual friends, frequenting her ever-changing places of work and recreation, and pitching our continued friendship to her as a new beginning in itself, I was able to keep her in my life.

As time passed, I observed her becoming increasingly uneasy. Her appetite for new novels became unmanageable. She would visit the library three, sometimes four times a day, often ringing me for assistance because she could not carry everything she was borrowing. She could no longer get past the first word of any book. If that word was an article, such as ‘The’ or ‘A’, she would want to write to the author, expressing her disappointment. In hysterical tones, she would decry the ‘death of the art of novel-titling’, and even began a philosophical treatise on the issue, which she abandoned within the hour.

At times, it should equally be known, she believed she had the best of it, pointing out that none of the literary characters she adored had ever died, killed themselves, or experienced tragedy. She frequently expressed how blessed she felt to live in a world whose only observable consistency seemed to be that nothing was ever over. Hence this, from her notebooks of 21st October, 2019:

Everything leads to other things!—and nothing is finished. In reality, there are no endings; only changes.

Accordingly, she had a huge admiration for the Greek philosopher Parmenides. His idea was that all reality was One, ‘unborn and unperishing’, Now and Continuous, meaning that ‘coming to be’ and ‘passing away’ were not creations or destructions but simple rearrangements. She viewed this idea as meaning that there was no such thing as an ending. Endings implied separate things, and so if all things were one thing then there would be no need for concepts such as time, plot, order, beginnings, middles or endings. It would be pure hyperbole to suggest Parmenides’ philosophy was embodied in Modán, and indeed I’m not sure such a statement would hold any meaning. But what I am sure of is that his philosophy expressed a way of experiencing the world more intense and true for her than anything else.

She became obsessed with discovering the secrets of Tumanay Khan: the direct ancestor of both Temüjin Borjigin (Genghis Khan) and Timūr Gurkānī (Tamerlane), two men who conquered enough landmass combined to outdo the efforts of Alexander the Great, Attila the Hun, Napoleon Bonaparte and Adolf Hitler all rolled into one. And both from the same bloodline! She had to know what was in the genes of Tumanay that compelled men to realise so fully the vision of the conqueror which, to her mind, was the ideal of infinite beginnings. New lands, new people, new lovers, new children, new skies, new wars again and again unceasingly from birth until death. She travelled from Peking to Baghdad through Kabul, and up to Moscow, and all the way to the gates of Vienna where Mongol hooves reached their limit, all the while consciously trying to construct the mindset of thousand-year-old Mongols, for whom these lands felt like the whole world.

In melancholy moments, she described literature as a ‘sunken chest’, which every time she dragged to the surface and opened, would only direct her to another sunken chest. She once complained that she was ‘excited by everything but understood nothing’. In similar spirits, I reprint this from one of her notebooks, dated 22nd October, 2019:

The world is but a series of doors, all to which I possess the key, but all which I know only open directly to other doors, infinitely, leading nowhere, except to other doors.

To me (without the eloquence of her written word) she merely remarked: ‘Life’s all foreplay’.

Without ever having enjoyed the emotional and psychological balm of catharsis, she never achieved that feeling in life – so precious to the rest of us! – of fulfilment. Nothing could ever be complete. Nothing would ever be in the past: submerged in the healing waters of retrospect.

I am quite aware that there is a sense in which the very writing of this introduction is a betrayal. Its tone, its tense, its attempt to condense or summarise a life: such a thing could only be written with the pervading implication of an ending.

The impact of her extraordinary vision will not be felt for years, perhaps decades. In fitting fashion, Katharine left us at the end of the beginning of her career. I take comfort in the knowledge that, to her mind, life was no more than its beginning anyway.

Katharine Modán died in 2020, at the age of 41.

L. E. Buffon

2020

Luke was born in Hammersmith, London, in 1992. He grew up in a suburb called Hillingdon and now lives in Highgate, North London. In recent years he has worked as a postman, a football coach, a legal recruiter and a tutor. He also holds a master's degree in philosophy. Luke has previously been published in The Journal of Compressed Creative Arts, Earth Island Journal, the Hillingdon Literary Festival Anthology and The Decadent Review.